Why Not Burn All the Tokens? Part I

In the age of the crypto boom, especially during the mass ICO wave of 2017–2018, thousands of projects launched their own tokens, promising a revolution in finance, decentralization, and technology. The crowd eagerly bought these assets simply because they were related to the crypto industry, which at the time was bringing impressive profits to its early adopters.

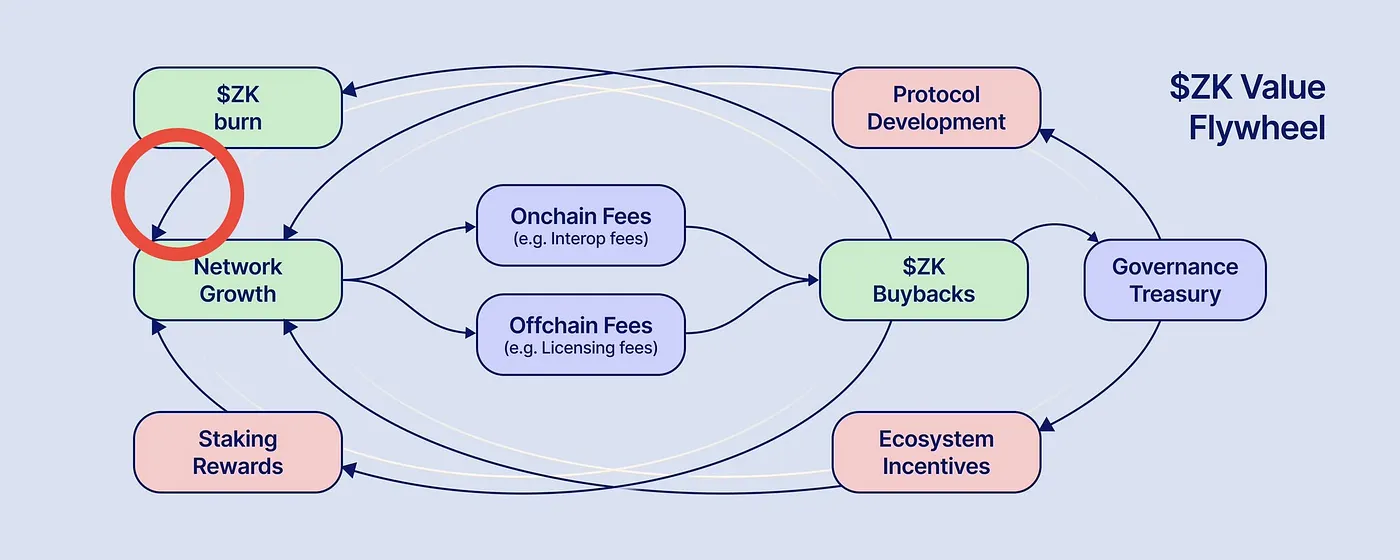

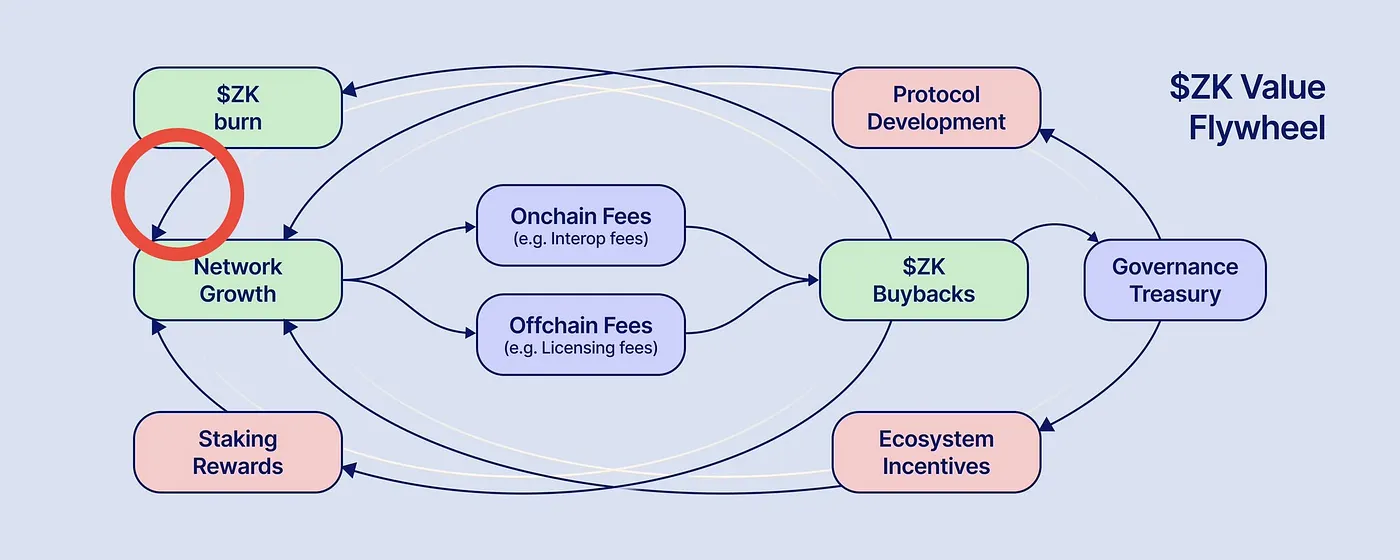

Skeptics were asking from day one: what are all these tokens actually for? The crypto industry ignored those questions and kept stamping out tokens one after another. But eight years have passed, and now, in 2025, we see a curious trend: the very same projects that once tried to convince buyers how “necessary” their tokens were are now announcing large-scale token burn programs. In November 2025, ZKsync founder Alex Gluchowski proposed a radical overhaul of the tokenomics: directing all network revenue into buying back and burning ZK tokens. He went even further, claiming this contributes to the growth of the network.

Gluchowski’s presentation

Uniswap’s creators are proposing essentially the same thing. Many other projects have been doing it for quite some time as well.

If tokens are now being burned in large quntities, was it worth issuing them in the first place? Let’s try to figure out whether tokens are needed at all, who they are actually useful for and why, and then try to understand what burning them is supposed to achieve.

What kind of value can tokens have?

How did the earliest projects that issued their own tokens explain their value? They didn’t. In 2017, the situation in the crypto market looked a lot like what we see in 2025. Bitcoin had reached unprecedented heights, and many people were experiencing FOMO. At the same time, it felt like buying bitcoin was already “too late”: it seemed too expensive.

And right in front of everyone were examples of crypto projects that were raising investment in bitcoin to fund their development, and in return offering their own cryptoasset. Those who bought into such assets (first and foremost Mastercoin and Ethereum) made solid profits. So it felt like there was a point in buying the tokens of pretty much any startup with the word “blockchain” or “cryptocurrency” in its name.

Hardly anyone at the time had a serious understanding of why bitcoin itself had value. Most people thought it was just a pyramid scheme you had to jump out of before it collapsed. If it was already “too late” to jump into bitcoin, the logic went, you had to look for other similar pyramids. That niche was filled by the ICO-era tokens.

Some token creators, however, did try to embed an economic meaning into their assets. The most common approach was to make them a key to access unique services offered by a new crypto project.

Utility tokens

These tokens can be compared to tickets in an amusement park. You come to the park, pay at the ticket booth, and receive little paper tickets that let you ride any attraction. Something very similar happens with a crypto project:

- we send the developer bitcoin (or ether, or stablecoins, or whatever else is accepted in the primary sale of the new tokens),

- we receive the project’s tokens,

- those tokens give us the right to use everything that will be launched within the project itself.

But why do we need such a two-step system? Wouldn’t it be easier to pay for each ride in the park with regular money? Why walk back to the ticket booth every time, buy a ticket, and then carry it back to the ride? Those are extra steps that could be avoided if you just paid in the usual money without any special “tokens”.

For the customer, yes. For the park operator, not really. To make direct payments at each ride, you’d have to equip every attraction with its own cash register and provide a separate secure cash storage for each one. It’s much simpler to sell tickets at the entrance.

It’s very similar to crypto projects. It’s easier for them if the developer accepts outside funds (fiat or crypto) in a centralized way, and gives out tokens whose circulation doesn’t have to be tracked by any “cash register”, because they never leave the confines of the project. And this is not just about accounting, but also about the technical implementation.

Reward tokens

Another economic use case for tokens was rewarding users for certain actions. If the developers of a crypto project don’t have a budget for a fully-fledged loyalty program, issuing their own tokens can help them incentivize users without spending real value on it. That’s where airdrops and retrodrops come from.

For users, those tokens usually have very little practical meaning. Still, they create a sense of belonging to a particular community, and that, too, is a kind of value. Even these tokens have markets, and on those markets there is at least some demand for them. And if that’s the case, why shouldn’t crypto projects issue them?

What’s important, though, is to issue them in volumes that are only large enough to satisfy that specific “collector” demand. There’s hardly a better word for it, even though in practice it is often not so much collecting as outright speculation. Tokens are bought in the hope that later they can be sold on to someone else at a higher price. But that’s already an unhealthy, unstable market.

Meme tokens

If there’s demand for tokens that give the holder absolutely nothing other than a symbolic expression of belonging to a project or its community, then why not create tokens whose primary purpose is exactly that?

That space was filled by meme tokens. Their creators deliberately don’t assign them any functional purpose and don’t bother inventing justifications for their value. Everyone knows that these tokens have no fundamental value, except symbolic one. If the meme symbolized by the token is popular in the crypto crowd, there is demand for the token. When that interest fades, demand disappears.

Sometimes the interest comes back again after a while. Sometimes even years later. And the blockchain keeps everything forever. So if token holders haven’t lost the keys to their addresses, they can sell those tokens to someone again.

Governance tokens

At the height of the DeFi boom, decentralized autonomous organizations became widely popular. The right to participate in such organizations is confirmed by holding special tokens. The more of them sit on your address, the greater the weight of your vote when making decisions about the organization’s future.

When one of the first such tokens, YFI, went parabolic in 2020, its creator Andre Cronje repeatedly stressed that the token had no intrinsic value. Maybe at that moment it really didn’t (even though the token’s price reached $45,000). But once a DAO governs a truly in-demand protocol, especially one generating substantial profit, those tokens start to gain very real value.

Difference between price and value

In some respects, governance tokens resemble traditional securities on the stock market — shares. If an organization is profitable, the desire to participate in its governance grows as well: to acquire a stake that gives you a seat on the “board of directors”.

Tokens backed by real-world assets

The most intuitive kind of value is found in tokens that represent a digital expression of rights to real-world assets.

The simplest example is stablecoins. Every USDC is backed by a real dollar, and every USDP is backed not just by a real dollar but by a dollar you can actually redeem by presenting your token to Paxos.

The same logic applies to tokens like XAUT and PAXG. Although not exactly the same: you’re unlikely to receive physical gold in exchange for PAXG, and even less so for XAUT. Still, these tokens represent very specific material claims, and that makes them genuine digital securities.

Hybrid tokens

Some tokens can be clearly classified into one of the types above. For example:

- FIL is used to pay for decentralized data storage in the Filecoin network — that’s a utility token.

- GST, the token that owners of StepN NFT sneakers earned for running or walking, is a reward token.

- SHIB is one of the most vivid examples of a meme asset.

- DYDX is a full-fledged governance token whose holders literally decide everything on the exchange (for instance, this week they voted to scrap fees on BTC and SOL perpetuals on dYdX).

- OUSG is a token whose value is linked to a basket of short-term US Treasury bills — a pure RWA example.

And then there are tokens whose value is tied to several of these aspects at once. For example:

- ARB is both a governance token (Arbitrum DAO) and a reward token (Arbitrum Incentive Program).

- CURVE is both a utility token (access to boosted rewards) and a governance token (voting on liquidity allocation).

- APE is both a reward token and a token used inside Yuga Labs’ games and metaverse.

There are actually more such hybrid tokens than tokens whose entire value rests on just one single aspect.

But if tokens can have real value, why burn them at all?

Why are tokens burned?

The trend of burning tokens was set by the creators of Binance Coin (BNB). BNB was launched as a utility token that gave users discounts on trading fees at the Binance exchange. But it doesn’t work quite the same way as those amusement-park tickets.

To better understand the difference, let’s compare BNB to another cryptoasset that also started out as a utility token: TRX. Not many people remember this now, but TRX was originally launched as an ERC-20 token. Its issuers promised holders that in the future it would gain access to the energy of the planned TRON blockchain. In the end, that’s exactly what happened. When the blockchain launched, the ERC-20 TRX tokens were swapped for TRX on the Tron network, and holders got the ability to use them to pay for smart contract execution on that chain.

That was just like the amusement park: the price of energy in TRX was fixed. How many “tickets” you bought, that’s how many times you could “ride” — use smart contracts. It didn’t matter how the TRX price changed between the time you bought it and the time you spent it to pay for energy.

BNB holders also gain access to certain “rides” in the Binance “amusement park” — namely, reduced trading fees on the exchange. But when you pay fees in BNB, the current exchange rate of BNB is taken into account. For example, if:

- a fee on the exchange for your usual trade is $1, and

- you bought 1 BNB for $100,

- you cannot be sure you’ll be able to pay the fees for exactly one hundred trades.

Because the “ride” prices are not fixed in BNB. Your “tickets” might lose value — or become more expensive.

- If the price of BNB falls to $10, your ticket will only be enough to cover fees for ten trades.

- If the price of BNB rises to $1,000, you’ll be able to pay fees for a thousand trades.

Those who use TRX strictly for its original purpose have no interest in seeing its price rise. (Think about it: would you be happy if ticket prices in your favorite amusement park suddenly went up?) Those who use BNB, on the other hand, are very much interested in seeing its price grow, because that way they can get more value from the tokens they already hold.

To support BNB’s price, Binance came up with a burn mechanism. Every quarter, Binance allocates part of its profit to buying back and burning tokens. This means that with every quarter, the number of BNB tokens decreases. And as long as Binance remains popular and traders want to pay its fees with the native token, demand for BNB remains. With steady demand and a shrinking supply, the price of BNB practically has to go up — which is exactly what we’ve seen in practice.

The success of BNB inspired many other crypto projects to try token burning as well. After all, it’s no secret that most tokens simply have no real buyers. Whatever mechanisms their developers built in to try to give them value, practice shows that the overwhelming majority of tokens aren’t needed by anyone.

Users come to rabbit.io fairly often with tokens they bought long ago and can no longer trade anywhere. They see that we support swaps for more than 10,000 cryptoassets and hope that their obscure token can also be exchanged for something. Yes, Rabbit.io really can swap rare tokens that other services don’t support. But even we aren’t magicians. You can swap 10,000 assets with us — but in total, there are millions of tokens out there. And almost all of those millions have no demand whatsoever.

Can burning help here?

When does burning make sense?

That’s a very important question, and I’ll try to answer it in the second part of this article. It will be published here exactly one week from now.