Self-Custody: The Illusion of Freedom — Part I

One of the greatest innovations introduced by cryptocurrencies is the ability to hold your assets yourself. Ask me what makes Bitcoin truly valuable, and I’ll tell you this: “The most valuable thing is that no one — not even the government — can take it away from me.” Many people feel the same. That’s why “self-custody” has become a buzzword in crypto marketing. It signals autonomy and control — and it works. The term grabs attention because people in crypto care deeply about it.

But what does self-custody really mean? At first glance, it sounds like a simple question: do you truly own what your wallet shows? Are you free to use your assets whenever and however you want?

Because that’s the key difference. With self-custody, you have freedom. Without it, what you have is a right — and every right requires someone else’s obligation. If that other party doesn’t fulfill their part, your “right” is just a polite fiction.

Behind the confident claims about self-custody, there often hides a fragile arrangement built on dependencies and trust. The term “self-custody” in today’s crypto world is not nearly as clear-cut as it seems.

A Chest of Gold vs. a Bank: The First Keepers of Wealth

It’s easiest to understand self-custody if we go back a couple of centuries and imagine a merchant returning home with his earnings — a pouch of gold coins — wondering where to hide them. If he stores the gold himself — under the floorboards or in a locked chest — that’s self-custody. If he takes the coins to a bank and receives a receipt in return (a kind of early banknote), that’s no longer self-custody: the coins are not under his control — the bank now holds them.

The value of that banknote depended entirely on the bank’s credibility. As long as the bank was trustworthy, all was well — the note could be traded at face value, just like the gold it represented. But if the bank collapsed, the note became worthless.

Banknotes: From Promises to State Power

But what about modern times? Would anyone today describe a banknote as a custodial financial instrument? Probably not — because the very nature of banknotes has fundamentally changed. The issuance of paper money is now regulated by governments. The right to issue banknotes has been transferred to central banks, and each note has become official legal tender. Its value is no longer backed by the gold in a vault — it’s backed by law.

Governments declare their currency must be accepted for payments within their jurisdiction. No one can legally refuse it for settling debts or buying goods. In countries like Austria and Switzerland, laws explicitly require businesses to accept physical euros or francs in cash. So if you know that everything for sale in your country can be purchased with those notes, why would you need the gold that once backed them? Not every seller accepts gold, but every seller accepts banknotes.

And when you store those banknotes in a safe at home — or even under your mattress — isn’t that essentially the modern version of keeping a chest of gold? The physical cash you keep personally is fully under your control. It looks a lot like self-custody: you’re not entrusting the note to anyone else, and you’re not relying on a bank or electronic systems. If you hide it well, neither the bank nor the government can take it away from you.

At home, you become your own bank: you ensure the safety of your money yourself, and you decide who gets the key to the safe. Some countries even emphasize the importance of that choice. For instance, Austrian and Swiss law protects the right of citizens to pay in cash as an alternative to digital transactions.

So, can we call keeping banknotes at home a form of self-custody? Most people probably would. What began as a certificate for custodial storage has arguably become the clearest modern example of self-custody — you’re holding something of value without intermediaries.

But there’s a caveat: governments are not eternal, and neither are their laws. The banknote that everyone is required to accept today might stop being considered money tomorrow. And when that happens, no one will be obligated to exchange it for goods or services.

You control the physical paper, but not what gives it value. The paper itself is worthless. Its entire worth comes from the state’s power — and willingness — to enforce its acceptance as money.

You can’t say the same about gold. For many participants in the market, gold holds subjective value, regardless of whether any government recognizes it or not.

So if the core question of self-custody is whether you truly possess the underlying value you see in your wallet, then depending on your perspective, even holding cash might not qualify. When you receive a banknote in exchange for your goods or labor, you’re doing something very similar to that old merchant who gave his gold to the bank: you’re handing over something with intrinsic value in return for a piece of paper whose worth depends entirely on the credibility of its issuer.

Money in the Bank: Who’s Actually Holding It?

Now, what about bank account balances? At first glance, this might seem like the closest modern equivalent to those old bank receipts the merchant would’ve received for his gold. We deposit something of real value (for many of us, that’s cash), and in return, we get numbers on a screen confirming our right to take that money back.

You don’t have direct control over the cash itself. But do you even need it? In many countries, the law requires that non-cash payments be accepted for settling debts, paying wages, or buying goods and services. Think about it: in your country, can an employee demand to be paid in cash? Or is it, vice versa, that the law requires wages to be paid via bank transfer?

If everyone is expected to accept bank payments — and perhaps even required to — then why bother with physical cash at all? It becomes almost as unnecessary as gold once banknotes were declared legal tender. And if the wealthiest people in the world have billions sitting in bank accounts, that doesn’t necessarily mean they can walk in and withdraw billions in cash. In fact, they usually can’t.

Modern bank money isn’t a promise to hand over something physical. It is the legal tender — just like cash, but far easier for governments to monitor and control. If the state freezes your bank account, then for all practical purposes, your money no longer exists. Sure, you might still see the balance on your banking app — but you won’t be able to do anything with it.

And what does “holding” such money mean today? It usually comes down to storing the data: your card number, your login credentials, and the devices where they’re saved. And that part, you do manage yourself. This isn’t the kind of custodial arrangement the old merchant had when he left gold in a bank vault. It’s something else entirely.

Imagine this: after a few too many drinks, you leave your phone unlocked at a bar with your banking app open. Someone transfers all your funds to a terrorist organization, which immediately cashes them out. Maybe you’ll eventually convince the authorities that you weren’t supporting terrorism — but will you get your money back? Probably not. It wasn’t being safeguarded by a bank — it was “stored” by you.

Still, despite this personal responsibility, you wouldn’t call it self-custody. Because while you may be the one “holding” the access, you don’t have the freedom to use the funds unconditionally. Your control is limited by systems and institutions — and that’s the difference.

Stablecoins: Digital “Banknotes” with a Twist

Now let’s carry that analogy over into the world of crypto. Suppose you own a stablecoin — a blockchain token pegged to the value of a fiat currency, like the US dollar. Take USD Coin (USDC), issued by the company Circle, as an example. If you’re a registered legal entity and have passed Circle’s compliance checks, Circle will actually commit to redeeming each USDC you hold for $1 in bank money.

That setup looks almost identical to historical examples of custodial banking. Whoever originally minted those USDC tokens gave something of real-world value — namely, bank money — in return. And the token itself represents a promise: Circle’s obligation to give back that bank money. The catch is that the redemption is only available to certain parties — namely, verified businesses that meet Circle’s compliance standards.

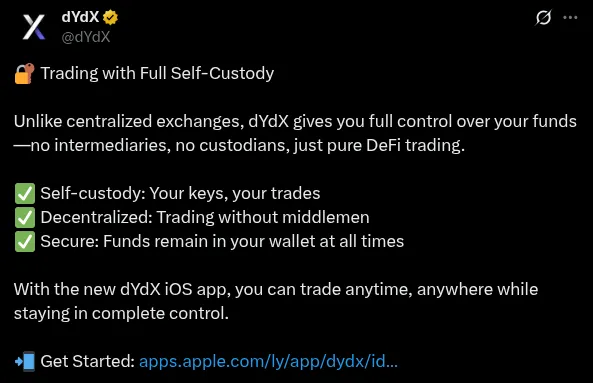

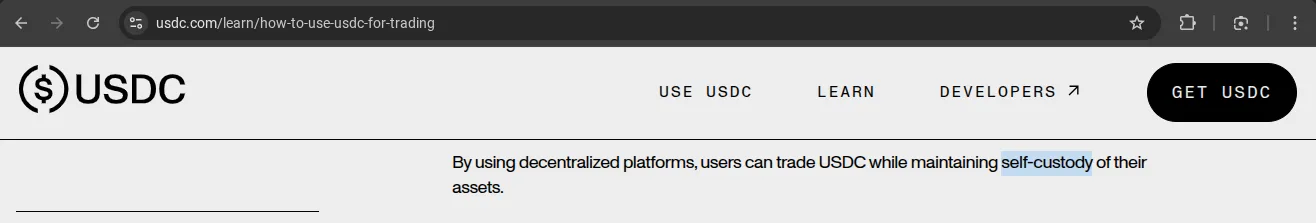

Is that self-custody? Definitely not. This is a classic example of custodial storage. So why do decentralized exchanges, where all trades are settled in USDC, claim to offer full self-custody?

Take this, for example:

And even USDC’s official website:

How can we talk about self-custody when USDC rests on what is essentially a third-order custodial structure?

Well, it’s the same dynamic we saw earlier: if you already have USDC, do you actually need those fiat dollars backing it? For most holders, the answer is no. The vast majority of USDC users aren’t registered corporations and haven’t passed Circle’s compliance review. So they can’t access the backing even if they wanted to.

And yet, USDC has real value for them. You can exchange it instantly for thousands of other cryptocurrencies on rabbit.io. You can spend it in hundreds of online stores that accept stablecoins.

The true strength of stablecoins like USDC lies in their liquidity. No one is legally forced to accept them, but many merchants do — because stablecoin payments are fast, cheap, and globally accessible.

So if you believe a stablecoin carries real, independent value — and not just as a claim on bank money — you might also call holding it in your wallet a form of self-custody.

Bridges and New Chains: Where Does Self-Custody End?

The crypto world is diverse and borderless: tokens can move between blockchains. Let’s say you hold USDC on Ethereum but want to use it elsewhere — maybe to post margin for perpetuals on dYdX Chain, Paradex Chain, or the trendy Hyperliquid network, where bridged tokens are the norm.

To make the move, you send your USDC to a bridge on Ethereum. There, it’s either locked or burned, and in return, you receive a “mirror” token on the target chain — essentially a receipt that says the original tokens are being held for you.

Here, we encounter another layer of custody: someone must be holding the original tokens while you use the bridged version. Sometimes that’s a smart contract, but in other cases it could be a multisig-controlled address managed by a company or group of validators. If something goes wrong — whether it’s a hack, an internal failure, or outright fraud — the bridge tokens can lose their value, because the underlying collateral is gone.

So by moving to another chain, you’ve added a new layer of trust. When your USDC was still on Ethereum, the chain of custody involved the issuer (Circle), the bank holding the reserves, and the fiat system. But once you cross the bridge, you also have to trust the bridge’s security — and the credibility of those who operate it.

Where does self-custody stop, then? Technically, you still control your bridged tokens — the keys are yours. But try finding liquidity for bridged USDC on dYdX Chain. Outside of the dYdX exchange itself, it’s practically useless. Even Circle won’t redeem bridged tokens — because they’re not its obligation, they’re the obligation of the bridge.

So when you move your funds into other blockchains — be it dYdX Chain, Hyperliquid, Paradex Chain, or some L2 solution — you still “hold the keys,” but not to the original asset. You hold a claim on a claim on a claim.

In the case of USDC, that looks something like this:

- At the base layer, physical cash is only valuable because the state enforces its acceptance.

- Bank deposits rely on that physical cash and are held at banks.

- USDC tokens on Ethereum are backed by those bank deposits and issued by Circle.

- Bridged USDC on other chains are IOUs from the bridge that claim to be worth the original USDC.

If steps 1 through 3 are backed by real-world utility or legal protections, step 4 isn’t. That final token’s value relies purely on faith in the bridge infrastructure. No backing from Circle. No legal recourse. Just code and trust.

So from any angle you look at it, that last step clearly falls outside the realm of self-custody.

Network Censorship: What If You Hold the Keys But Still Can’t Spend?

Self-custody means you hold the keys. With the keys, you can sign transactions. But here’s the catch — just because you can send a transaction doesn’t mean the network will process it.

Validators or miners on a blockchain can refuse to include your transaction in a block. And if the network doesn’t let you become a validator yourself — or makes that path practically inaccessible — then there’s very little you can do to push back.

In some blockchains like Hyperliquid and Paradex Chain, the validator set is small and tightly interconnected. In other networks, joining as a validator requires being approved or delegated by someone who’s already inside the circle. That kind of gatekeeping prevents independent actors from entering and helps preserve validator collusion — making transaction censorship much more likely.

So here’s the hard question: What good is self-custody if the network won’t let you use your assets? It’s a serious issue. Self-custody guarantees that you alone control the keys — but the freedom to transact depends entirely on the decentralization and neutrality of the network.

If the blockchain is centralized or governed by a cartel, your wallet can turn into a gilded cage. Your funds are technically yours, but using them requires permission from unseen gatekeepers.

That’s why self-custody only truly works on networks that are resistant to censorship — and ideally only for assets that have real, independent value, not just claims on someone else’s obligation.

The Ideal of Self-Custody — Is It Bitcoin?

At this point, it might seem like all these problems only apply to tokenized assets and tightly regulated blockchains. But what if we’re talking about Bitcoin — an asset whose value doesn’t depend on anyone’s promise, and a network where anyone can become a miner, provided they’re willing to pay for ASICs and electricity?

In that case, surely there’s no room for self-custody issues… right?

Well, not quite. Even within the Bitcoin ecosystem, some services claim to be “non-custodial” in their marketing — but in practice, they don’t offer the kind of freedom you’d expect from Bitcoin.

To be fair, the challenges in Bitcoin are very different from what we see with stablecoins on exchange-centric blockchains. They’re not about hidden custodians or multi-layered trust structures. But they exist nonetheless — and they’re worth exploring.

I’ll cover those issues in the second part of this article.

It will be published here next week.

Follow to stay tuned.