Governance Tokens: How Democracy Works in Crypto

When blockchain technology first emerged, one of its most promising applications was transparent, verifiable, and tamper-proof online voting.

Today, the most widespread real-world implementation of that idea is governance tokens — digital assets that allow users to vote on decisions within decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs).

But the further this concept develops, the more questions arise. Is the idea of blockchain-based governance actually evolving in the right direction?

This article explores the challenges and prospects of governance tokens.

What Are Governance Tokens For?

A cryptocurrency that develops in a decentralized manner can easily exist without governance tokens. A prime example is the Bitcoin community, which has evolved successfully without any special governance token. When a protocol update is proposed, each node operator decides individually whether to support it or not. The network can exist in multiple versions at once — and that doesn’t bother anyone. Everyone simply follows the path they believe is correct. Those who run full nodes and store the entire blockchain locally rely on their own data as the ultimate source of truth. If neighboring nodes adopt changes that I don’t agree with, I can just trust what my own node considers valid. That’s how financial sovereignty works.

In theory, any cryptocurrency ecosystem could operate the same way. Each node relies on the blockchain data that its built-in verification algorithm deems correct. Anyone who wants to implement changes can go ahead — and as long as those changes don’t violate the original consensus rules, all participants can continue interacting. This is a crucial property for any cryptocurrency that aims to be a long-term project.

Imagine this: Satoshi Nakamoto turns on his old computer 15 years later, runs his original copy of Bitcoin Core, and sends some BTC. What’s the right outcome?

- That the transaction goes through successfully (as is the case with Bitcoin today),

- Or that the protocol has changed so much that old-style transactions are no longer valid?

Most likely, when it comes to managing our own assets, we’d prefer to rely on the rules we originally agreed to — not those that were later imposed by a majority. Otherwise, how would storing cryptocurrency differ from storing money in banks that come up with new requirements to prevent us from freely managing our money?

But things change when a project creates a shared treasury that needs to be managed collectively. If a cryptocurrency ecosystem includes a common fund, decisions about how to use that fund must be made together. Otherwise, the project risks becoming overly centralized — governed by one or a few individuals.

Consensus among thousands of people is practically impossible. There will always be disagreements. So a more formal mechanism is needed: voting.

But voting with actual cryptocurrency — say, sending BTC to the address associated with one of the choices — introduces a problem: you’re literally paying to vote, and not everyone will want to do that.

As a compromise, a project can issue governance tokens: special-purpose tokens with no intrinsic value, used solely for voting.

I said these tokens have no intrinsic value — and that’s true. By themselves, they’re worth nothing. But the right to vote gives them value.

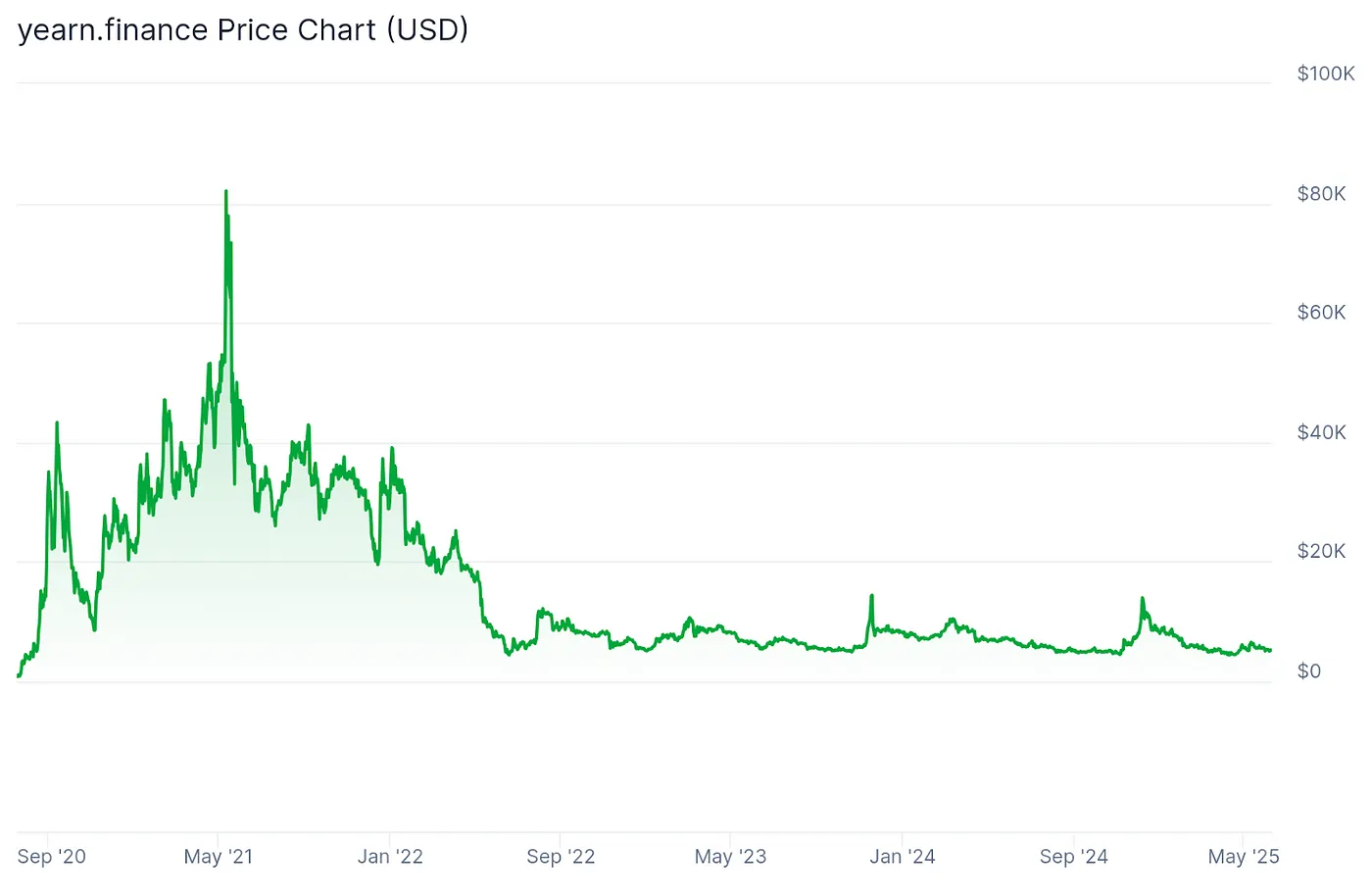

A great example of this is YFI — the governance token of the Yearn Finance protocol. When its price soared from zero to $40,000 in 2020, Yearn’s developer André Cronje emphasized publicly that YFI had no intrinsic value and granted no income or dividends. He made that clear to discourage people from buying it as an investment. But people started buying it anyway — precisely for the right to participate in governance. And that’s what gave it market value: a few months later, it peaked at $80,000 per token.

YFI/USD chart. Source — Coingecko.

Ironically, most YFI holders still didn’t participate in governance. So the token’s value was largely speculative. But this is how the idea of governance tokens took shape — at the intersection of:

- the need for decentralization,

- the challenge of managing shared funds, and

- the search for a convenient voting mechanism.

Power in DAO: Not Where You Expect It

In an ideal world, a governance token holder is like a shareholder who attends meetings and votes “for” or “against” key decisions. In practice, the range of issues put to a vote is quite broad. It includes not only the use of treasury funds but also protocol upgrades, functionality changes, partnership approvals, and fee settings.

Simply put, the community attempts to guide the platform’s strategic direction through tokens. For example, UNI holders vote on whether to allocate grants from the Uniswap treasury, and MKR holders decide whether to adjust interest rates on loans in MakerDAO.

It sounds great: everyone who holds a token becomes a co-owner of the ecosystem.

But here’s the catch — does everyone actually want that kind of democracy? Imagine if every bank depositor voted on what interest rates to set on loans, or if every driver voted on highway speed limits. Most people simply don’t have time for that.

A similar pattern emerges in blockchain governance: many token holders don’t bother to vote. Voter apathy is a serious issue for DAOs — often caused by a lack of interest, time, or belief that one vote can make a difference. As a result, quorums are barely met, and decisions end up being made by a small number of highly active (or highly wealthy) participants.

But even those with the most tokens — and therefore the greatest stake in the protocol — often choose not to participate.

In May 2025, Arbitrum DAO proposed lowering its quorum requirement from 5% to 4.5% of ARB tokens, precisely because of chronic low turnout. Participation rates had hovered between 4% and 5%. Without lowering the threshold, the DAO risked grinding to a halt — effectively becoming non-functional.

So who’s really in charge if ordinary token holders don’t care to govern?

Developer Jengajojo, who contributed to a Uniswap governance improvement proposal, shared one telling example. In Nouns DAO, representatives of well-known trader DCF GOD accumulated control over a significant number of tokens and proposed liquidating the entire treasury — worth $27 million.

A more extreme case occurred in Beanstalk in 2022. An attacker took out a flash loan, used the funds to instantly acquire a controlling share of governance tokens, and immediately voted to transfer the entire treasury to their own wallet. While honest participants came to their senses, the attacker approved and executed the proposal — walking away with $182 million, repaid the loan, and vanished. The DAO was left with nothing.

Another case, highlighted by crypto analyst Ignas on April 8, 2025, involves hitmonlee.eth, a user who spent just 5 ETH (around $10,000) through the LobbyFi platform to gain access to votes representing 19.3 million ARB tokens — enough to influence assets worth $6.5 million.

The newly elected committee member supported by hitmonlee.eth would receive: a salary of 66 ETH per year, and potential bonuses of 100,000 ARB, all secured by a 5 ETH investment.

In all these cases, voter apathy became a vulnerability. The DAO simply couldn’t defend itself — not through code, not through coordination.

So what do governance tokens really control?

Mostly, they control money — the project’s shared resources. And that creates a natural magnet for clever opportunists who know how to exploit the system for personal gain, while regular holders remain mostly indifferent.

Just like most people have no interest in voting on the technical design of a payment app, most token holders don’t want to micromanage protocol development.

The Pitfalls of Tokenocracy

Aside from the fact that a DAO managed through tokens can turn into a “parliament” where seats are bought and only five out of a hundred participants show up to vote — making decisions that benefit themselves — several more pitfalls stand out:

- Whale power. The system of “the more tokens you have, the more your vote counts” leads to large holders being able to disproportionately influence the outcome. In some projects, just 1–2% of addresses control 90% of the voting power — effectively, oligarchs make the decisions while smaller participants are reduced to voting for show. This undermines the very idea of decentralization.

- Speculators over supporters. Another oddity: governance tokens are actively traded, which means they attract not just committed community members but also opportunistic speculators. Some may even propose deliberately controversial or unpassable votes (like distributing the entire treasury to token holders) just to stir up interest, pump the token’s price, and dump it at the peak. As a result, some proposals resemble insider market games more than genuine collective decision-making.

- The illusion of decentralization. Perhaps the most disappointing pitfall is when governance exists only on paper. The tokens are there, the votes are happening — but real power still lies with the project team.

A striking example of the last pitfall is the Arbitrum DAO scandal in 2023.

The developers proudly announced the launch of community governance — but right away, a disturbing fact surfaced: the Arbitrum Foundation unilaterally appropriated 750 million ARB tokens (worth about $900 million) from the treasury, without community approval. When the community found out, the foundation tried to legitimize the move retroactively with a vote — which unsurprisingly failed. In response, the team stated that the vote was merely symbolic and that the decision had already been made.

The project was immediately accused of performing “decentralization theater” — decentralization in name only. Turns out, you can distribute tokens and claim to be democratic, but if the developers aren’t ready to truly listen to the community, the entire governance model becomes an empty performance.

As we can see, the problems are many. In such conditions, I might have concluded long ago that governance tokens are a failed experiment — and if I had any, I’d exchange them for something more promising.

Some people really do that. They come to rabbit.io and trade UNI, AAVE, or CRV for something that seems more solid in current market conditions — like BTC, XAUT, or even HYPE.

But others do the opposite. They come to rabbit.io and exchange stablecoins like USDT or USDC for far more volatile governance tokens — DYDX, COMP, or ONDO.

And I don’t think our clients are foolish. If they come to rabbit.io looking for governance tokens, it means they see something in them — a potential that’s still alive, despite all the flaws.

The Future of Governance Tokens

Despite their many challenges, DAOs aren’t going anywhere — and governance tokens are here to stay. Today, they’ve become almost a must-have feature for any new DAO. And it’s not hard to see why.

Going back to the starting point, one important thing stands out:

In Bitcoin, every full node independently verifies whether each transaction and block complies with the protocol rules. If a node believes a block violates the rules, it simply rejects it — and no authority can force it to do otherwise. Everyone in the ecosystem understands that breaking the rules is pointless, so no one does — and the result is that all nodes maintain the same blockchain.

But when the rules are set not by each participant (for themselves), but by a majority (for everyone), there has to be a way to decide who gets to define that majority.

Tokens that are distributed simply for using the platform have proven to be a weak foundation for majority rule. Users and active contributors are often very different groups — and mixing them under one label of “token holder” blurs the line between governance and speculation.

Still, the problem isn’t the tokens themselves — it’s how they reach their holders. If airdrops don’t work, maybe it’s time to try something else?

And there are other models.

First, the concept of governance mining rewards tokens not for usage, but for real contributions — writing code, drafting proposals, moderating discussions. This shifts voting power toward those who are actively helping the protocol grow.

Second, the delegated model is gaining popularity. If you don’t have time to dive into every issue, you can delegate your vote to someone you trust — an expert who will vote on your behalf. This approach addresses voter apathy among smaller holders while keeping formal control within the community.

Third, projects are experimenting with hybrid schemes. Some are introducing quorums and thresholds to prevent random holders with 0.1% of tokens from submitting spam proposals. Others are trying quadratic voting, where the weight of a vote increases more slowly than the number of tokens — helping to reduce whale dominance.

In the future, we may see governance models where voting power depends on experience, contributions, or other reputation-based factors — not just token balances. But even then, a token can remain a useful formal proof of eligibility to vote.

The idea of governance tokens isn’t broken — the crypto industry just needs to learn how to use them wisely.