Why a 51% Attack Isn’t as Scary as It Sounds

This week, the Monero network found itself under a 51% attack. The Qubic project claimed it had gained control over the majority of Monero’s mining power — and backed it up by successfully rewriting several blocks. That sounds alarming: after all, many people believe a 51% attack spells doom for any cryptocurrency. But the reality is far less dramatic. As the Monero case shows, even when an attacker temporarily gains majority hashpower, it doesn’t mean the network collapses. The blockchain kept running, the XMR price barely dipped, and life went on. So let’s break down what a 51% attack really is, why it’s not the end of the world, and what past incidents have taught us.

What Is a 51% Attack — and What It Can’t Do

In simple terms, a 51% attack happens when a coordinated group of miners controls more than half of a blockchain’s total computing power. This allows them to mine new blocks faster than the rest of the network combined.

Under normal conditions — when mining power is distributed among many independent miners — everyone who finds a new block wants to announce it to the network as quickly as possible. If they delay, another miner might publish a different block at the same height, and it’ll be a race to see which version ends up in the official chain and which one gets discarded.

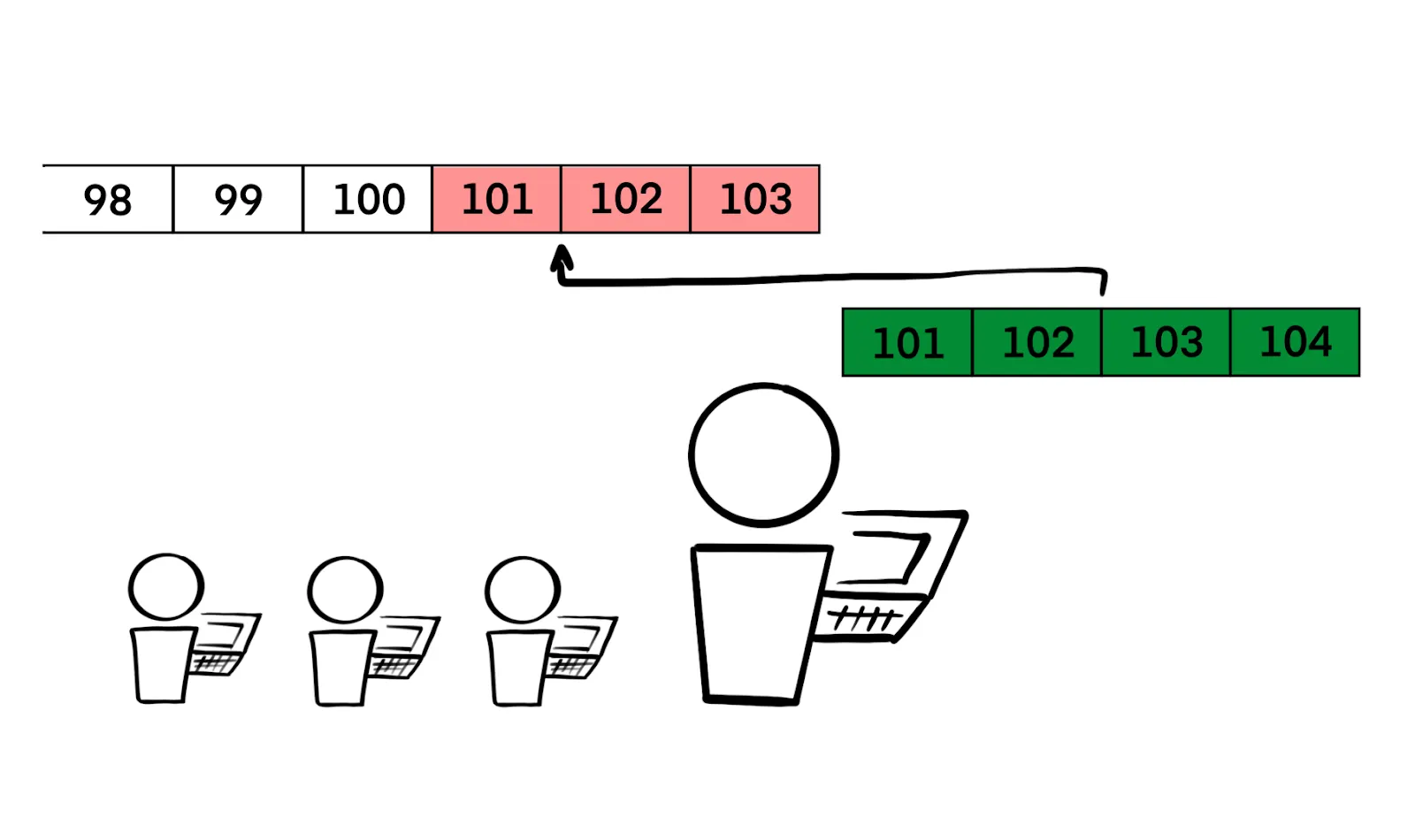

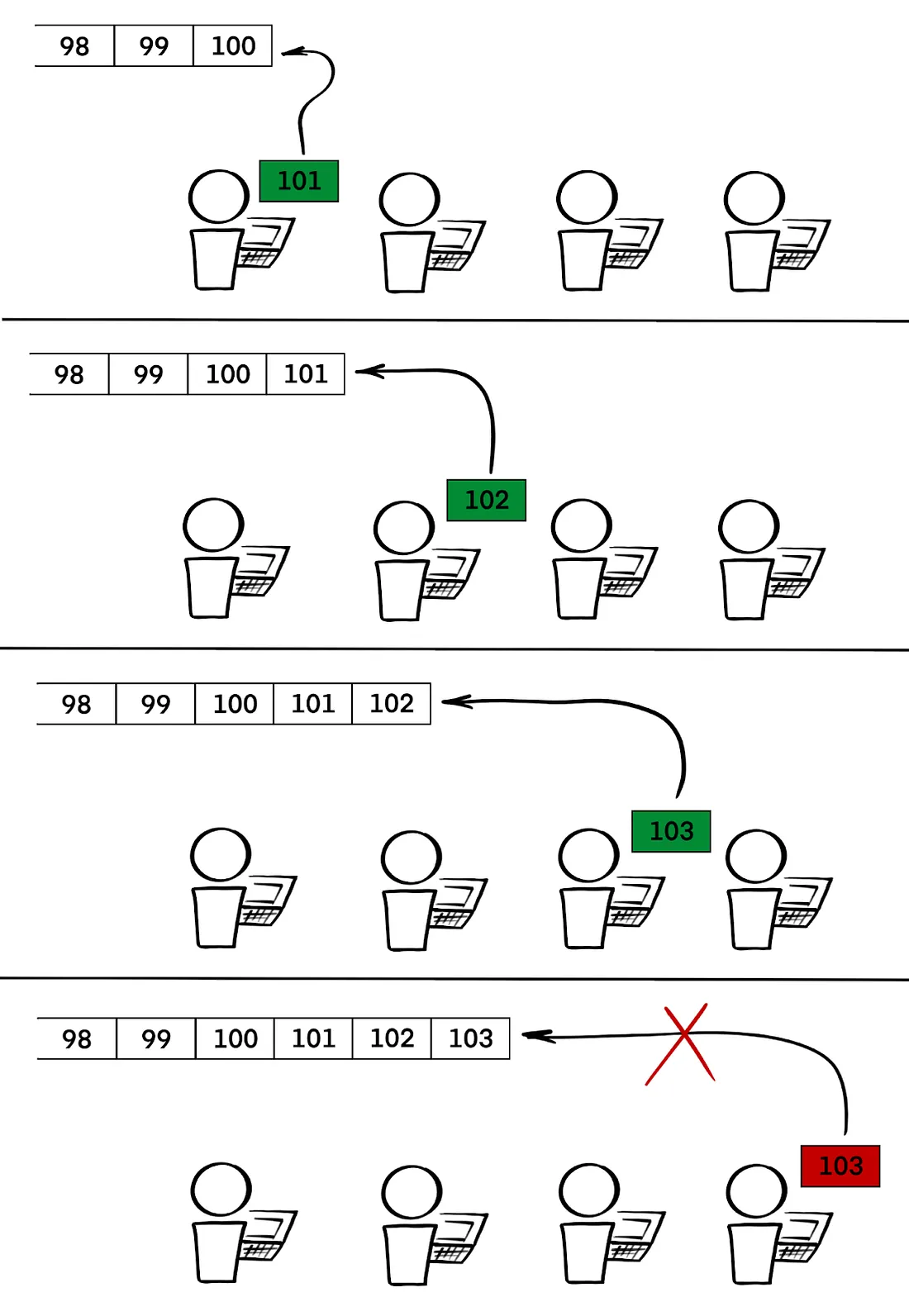

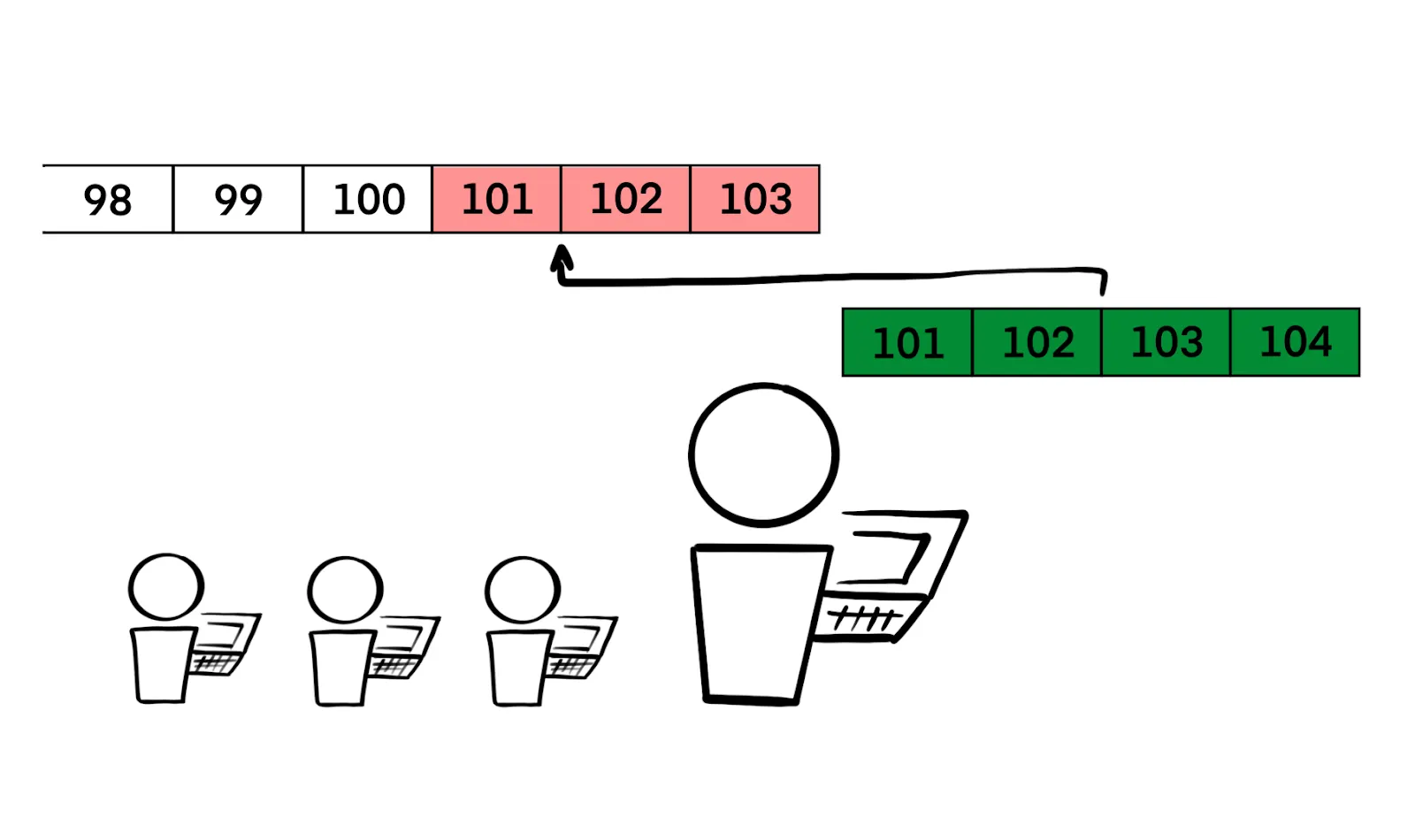

But if one miner has more hashpower than everyone else combined, they can afford to stay silent. Instead of immediately broadcasting their blocks, they can secretly build an alternate version of the blockchain. Later, they release their longer chain all at once — and the network, following the rules of Proof-of-Work, will accept it, since it represents the greater total work.

This means the attacker can undo previously confirmed blocks. Imagine you received a crypto payment — and then found out the block it was in has been dropped from the chain. Your coins are gone, and they’ve been returned to the person who originally sent them.

So what can a 51% attacker actually do?

- Reverse confirmed transactions, including their own, to perform double spends.

- Censor transactions, by excluding ones they don’t like from the blocks.

But let’s be clear about what a 51% attacker can’t do.

- They can’t forge transactions or steal coins that don’t belong to them — they don’t have your private keys.

- They can’t reverse payments they sent before they started building their secret chain — only blocks created after they began the attack can be rewritten.

- They can’t “break the protocol” or rewrite the rules of the blockchain. Even if they try mining empty blocks (with no transactions), they can only freeze the network temporarily.

In the end, controlling a majority of hashpower is not a magic wand. It only gives the ability to reorganize the most recent pages of the blockchain.

The Monero–Qubic Incident: No Panic Needed

Let’s get back to the Monero drama. The Qubic project managed to take control of over 51% of Monero’s hashpower — not through brute force, but by creatively incentivizing CPU miners. Qubic offered rewards in its native QUBIC tokens to those who mined Monero through its own pool. As a result, Qubic’s share of Monero mining jumped from just 1.5% in May to over 25% by the end of July. Then, on August 12, they announced they had crossed the 50% threshold. In the span of just four hours, Qubic mined 63 out of 122 Monero blocks — slightly more than half.

So what did they actually do with that power? They carried out a chain reorganization six blocks deep. There were no detected double spends, no censorship attempts — just a demonstration of Monero’s vulnerability. It was more of a proof-of-concept than an economic attack.

The Monero community didn’t take it lying down. In response, someone launched a DDoS attack on Qubic’s infrastructure. The hashpower from Qubic’s miners dropped by more than two-thirds, pushing them from first to seventh place among Monero mining pools — at least for a few hours. Qubic later recovered and once again claimed majority hashpower, but by that point, the panic had largely subsided. People had seen that nothing catastrophic had actually happened.

And what about the price of Monero? Many expected a crash — after all, trust in the network had seemingly been shaken. But in reality, XMR barely dipped. At the height of the incident, Monero dropped by around 7–8%, which is within the range of normal daily volatility for altcoins. And the very next day, the price rebounded 11% from its local low. Holders weren’t panicking. They understood that the attack was temporary and hadn’t fundamentally broken anything in Monero.

At Rabbit Swap, we didn’t observe anything out of the ordinary either. There was no trading frenzy, no drop-off in Monero swaps. XMR remained one of the most popular assets on rabbit.io. And the chain reorganization didn’t even noticeably affect swap speeds — as we require 12 to 15 confirmations per transaction, and Qubic never reorged that many blocks at once.

The community, in a sense, got a wake-up call — and a kind of immune boost. Now it’s clear: even a “successful” 51% attack isn’t nearly as dangerous as people assume. Still, the lesson is useful: decentralization matters, and users might want to avoid mining with pools that get too large.

Notable 51% Attacks and What Happened After

51% attacks aren’t new. They’ve happened before — mostly to smaller blockchains where controlling the majority of hashpower is relatively easy. We’ve seen successful attacks on Verge, MonaCoin, Vertcoin, and Litecoin Cash back in 2018–2019. Bitcoin Gold (BTG) was also targeted twice — once in 2018 and again in 2020 — with combined losses exceeding $18 million.

But let’s take a closer look at two particularly important cases.

Ethereum Classic (ETC), 2020

In August 2020, Ethereum Classic suffered a series of deep 51% attacks. At one point, attackers managed to reorganize more than 7,000 blocks — that’s about two full days of transactions. Real double spends took place, with recipients reportedly losing around 807,000 ETC (worth about $5 million at the time).

You’d think that kind of attack would destroy all trust in the network — but it didn’t. ETC survived. And even more surprisingly, the price barely moved: after the worst attack, ETC was trading around $6.86, just 4% lower than before. Markets largely shrugged it off.

The bigger reaction came from infrastructure providers:

- OKEx threatened to delist ETC due to repeated attacks.

- Coinbase increased ETC deposit times to 2 weeks, to reduce the risk of confirming transactions that might later be reversed.

Ethereum Classic developers responded by introducing updates and reaching out to friendly miners to help stabilize the network. Despite being labeled as vulnerable, ETC still operates today and remains in the top 50 cryptocurrencies.

Bitcoin SV (BSV), 2021

In 2021, Bitcoin SV — a fork of Bitcoin — faced a bizarre situation: not just one, but several overlapping 51% attacks. How is that even possible? After all, each attacker is supposed to need a majority of hashpower.

In BSV’s case, a single unknown miner launched multiple competing chains simultaneously. At different points, they would publish different versions of the blockchain. As a result, there was chaos. Different nodes were following different “correct” chains.

The BSV Association eventually recommended a drastic fix: manually configure nodes to reject blocks from the attacker. This meant temporarily overriding the network’s default rules. Not everyone agreed to this — some nodes followed one chain, others followed another. But once the attacker stopped, the usual “longest chain wins” rule was restored. Nodes resynchronized, and BSV kept running.

So why was BSV vulnerable? Because it uses SHA-256, the same mining algorithm as Bitcoin — but with a fraction of the hashpower. That made it relatively cheap for an attacker to rent or redirect SHA-256 miners and target BSV. Despite the humiliating attack, BSV didn’t die. Its reputation took a hit, but the coin still trades today — and is still available on rabbit.io. During the attack, the price fell — but not catastrophically. Holders remained surprisingly calm, waiting for the chaos to pass.

On one hand, it’s hard to imagine anyone trusting a network where confirmed transactions can be silently undone. But on the other hand, most of these attacks targeted small networks — fringe coins with low hashpower that people never treat as secure stores of value. The market often reacts with a shrug.

Things would be very different if someone tried this on Bitcoin — but that’s essentially impossible. The cost of such an attack would be astronomical and completely uneconomical. In contrast, smaller chains are often attacked using rented hashpower from mining marketplaces — it’s cheap and easy.

That’s what makes this week’s Monero story so interesting. It’s a rare example of a popular cryptocurrency falling victim to a real 51% attack. And what’s more, the attack showed that you don’t even need to rent or buy massive hashpower. You can crowdsource it by offering people basically useless tokens as an incentive.

Which raises a sobering thought: if that’s possible, then maybe no network is truly safe — not even Bitcoin.

A Successful 51% Attack on Bitcoin — From the Inside

Technically speaking, even Bitcoin has experienced a 51% attack. But in this case, it didn’t come from malicious actors — it came from Bitcoin’s own developers, trying to save the network.

In August 2010, a critical bug was discovered in the Bitcoin codebase. It allowed someone to create a transaction with two outputs of 92 billion BTC each. Yes, seriously — block #74638 included a transaction that sent a total of 184,467,440,737 BTC to three different addresses. This broke everything: it violated the 21 million BTC supply cap, disrupted consensus, and threatened to kill Bitcoin before it ever had a chance to succeed.

But Satoshi Nakamoto and other core developers acted fast. Within five hours, they released a patch that fixed the bug and prevented such malformed transactions. They then urged miners to start building on top of block #74637, effectively replacing block #74638 and eliminating the invalid transaction from the blockchain.

Earlier in this article, I said that a 51% attack can’t reverse blocks that were confirmed before the attack began. But in this case, developers were able to do exactly that — because the patched version of the chain was supported by an overwhelming majority of the network’s hashpower. That gave it the ability to overtake the “bad” chain, which had a five-hour head start. Once the corrected version grew longer, the rest of the network adopted it, and the invalid coins vanished. Bitcoin was saved.

Of course, this happened when Bitcoin’s hashpower was still tiny, and the community was small and tightly knit. Convincing most miners to go along with the rollback wasn’t difficult — especially since Satoshi himself was still actively mining and had significant influence. But the precedent is important: no one looks back at this event with horror or calls it an “attack” in the usual sense. Bitcoin survived — and went on to thrive.

A 51% attack is a tool — not good or evil by itself. It all depends on who’s wielding it. Bad actors may try to exploit it for profit. But honest participants can also use it, as a last resort, to protect the network.

In the end, blockchains aren’t just code — they’re communities. And if a community is strong and well-organized, it can withstand attacks — or even fight back with the same tools.

Why 51% Attacks Rarely Lead to Disaster

In the original Bitcoin whitepaper, the 51% attack is acknowledged as a theoretical problem — one that the author admits has no clear solution. Ever since, the concept has carried a kind of mythical weight: a threat so fundamental that it feels unstoppable and terrifying by default.

And after reading everything in this article, you might find yourself wondering:

What if intelligence agencies have been secretly mining parallel chains of every major cryptocurrency for years, just waiting for the right moment to publish them and undo all transactions — wiping out crypto history to the delight of governments and regulators everywhere?

That’s a scary thought. But in practice, it’s almost impossible.

Pulling off a long-term 51% attack is incredibly expensive. You either need:

- an overwhelming amount of computing power (in Proof-of-Work), or

- to buy up more than two-thirds of all staked coins (in Proof-of-Stake networks).

In Bitcoin, for example, maintaining 51% of the network would cost tens of billions of dollars in hardware and electricity. Sure, maybe an intelligence agency could hide that kind of operation — at least the machines and the power usage. But in Proof-of-Stake systems like Ethereum there’s no hiding. All stakes are visible on-chain. No agency can secretly accumulate 67% of the validator set without everyone noticing.

The Monero attack this week was estimated to cost $75 million per day to sustain. That doesn’t mean Qubic literally lost $75 million a day. The point is: whether you publish each block right away or hold them all back for a day, your energy and infrastructure costs are the same. What changes is risk. While you’re holding back blocks, the community might respond — they might onboard new miners or cut off your network access. If they succeed, you’ve wasted all your work and your chain never gets accepted. In that scenario, the attacker eats the full cost — potentially tens of millions — with no payoff. So $75 million isn’t a daily loss, but it is the upper limit of the risk. And few can afford that level of risk — especially if they’re trying to carry on the attack for weeks or months.

That’s why even “successful” 51% attacks — like the one we just witnessed — tend to be short-lived and ultimately inconsequential. They shake things up for a moment, maybe cause some drama, but in the end, the network recovers, the damage is limited, and the long-term impact is minimal.

The myth of the 51% attack is scarier than the reality.