How Crypto Swaps Help Avoid Tracking

All records of cryptocurrency transactions are stored in blockchains, most of which are publicly accessible. This means that anyone can view and analyze almost any action taken with nearly any cryptocurrency at any time.

Who Tracks Crypto Transactions and Why

The main parties interested in tracking a transaction are the sender and the receiver. They use blockchain explorers to ensure:

- The transaction went to the correct address.

- The amount and assets match what was agreed upon.

- The transaction was successful and didn’t get stuck in unconfirmed status.

At Rabbit Swap, both we and our clients rely on this type of tracking to confirm everything went smoothly with their swaps.

If you’ve ever used a blockchain explorer, you might have felt tempted to play detective,

- looking up other transactions associated with the address you sent your crypto to,

- checking its balance,

- or seeing what other addresses it has interacted with.

Blockchain explorers allow for all this in just a few clicks. And with additional tools, you can even set alerts to notify you when the cryptocurrency you sent moves to another address. Services like Blockseer enable users to essentially “follow” the path of cryptocurrency, visualizing connections between addresses involved in transactions.

People track crypto transactions for various reasons:

- Some out of simple curiosity.

- Some professionals investigate “dirty” financial flows to stop them.

- Malicious actors might track cryptocurrencies to identify large balances, intending to target the owners with blackmail, social engineering, or threats.

This latter risk is only possible if an address can be connected to an individual. However, identifying individuals from their crypto addresses is not as difficult as it may seem. To receive cryptocurrency, users share their addresses, which makes the trail hard to avoid.

Identifying Address Owners in Blockchain Analytics

Many addresses are available in public sources:

- On websites of vendors accepting cryptocurrency,

- On donation platforms,

- In social media or forums.

Even if an address was shared privately, that communication could be hacked, revealing the owner’s identity. And if one of your addresses is linked to you, advanced analytics systems can potentially trace other addresses belonging to you as well. For instance, the blockchain analytics company Chainalysis claims it has identified addresses of over 65,000 entities.

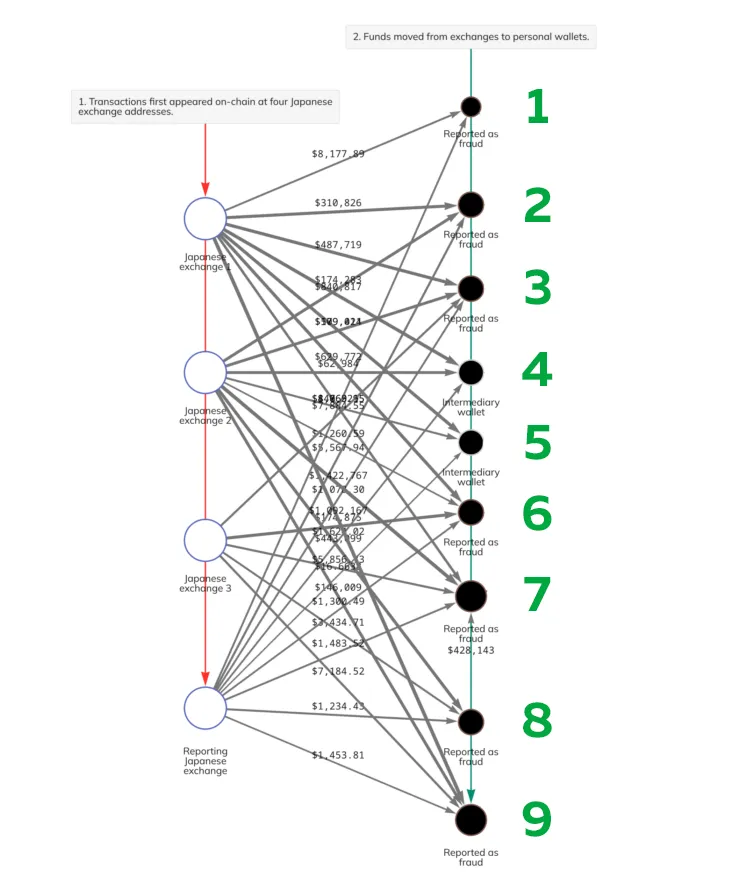

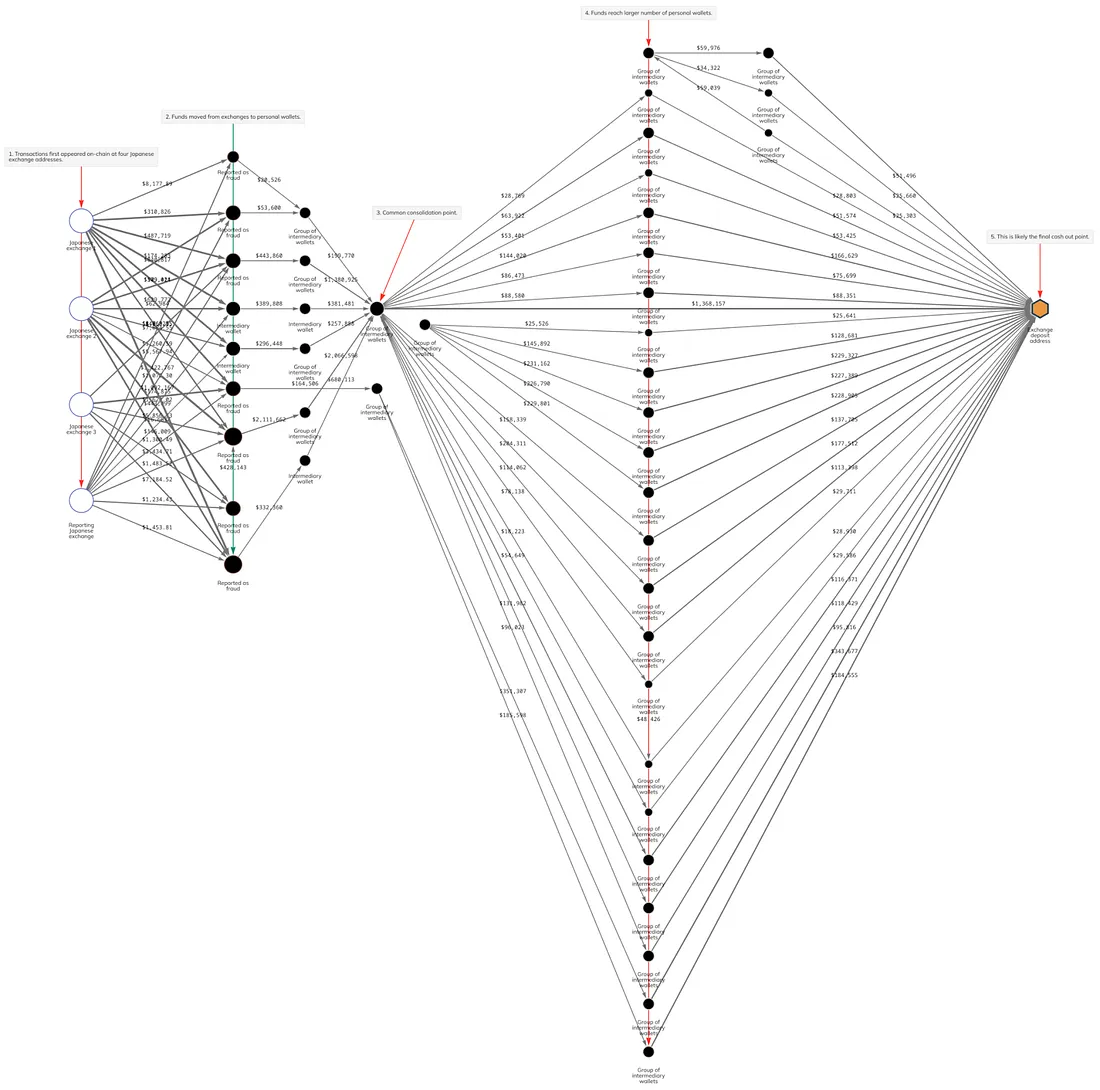

Chainalysis shared an example case that illustrates how they analyze transaction networks. The case involved:

- Fiat money deposited into four accounts on a crypto exchange, which were then exchanged for crypto and transferred to multiple addresses.

- Chainalysis’s task was to trace the final beneficiary.

Here’s how the investigation unfolded.

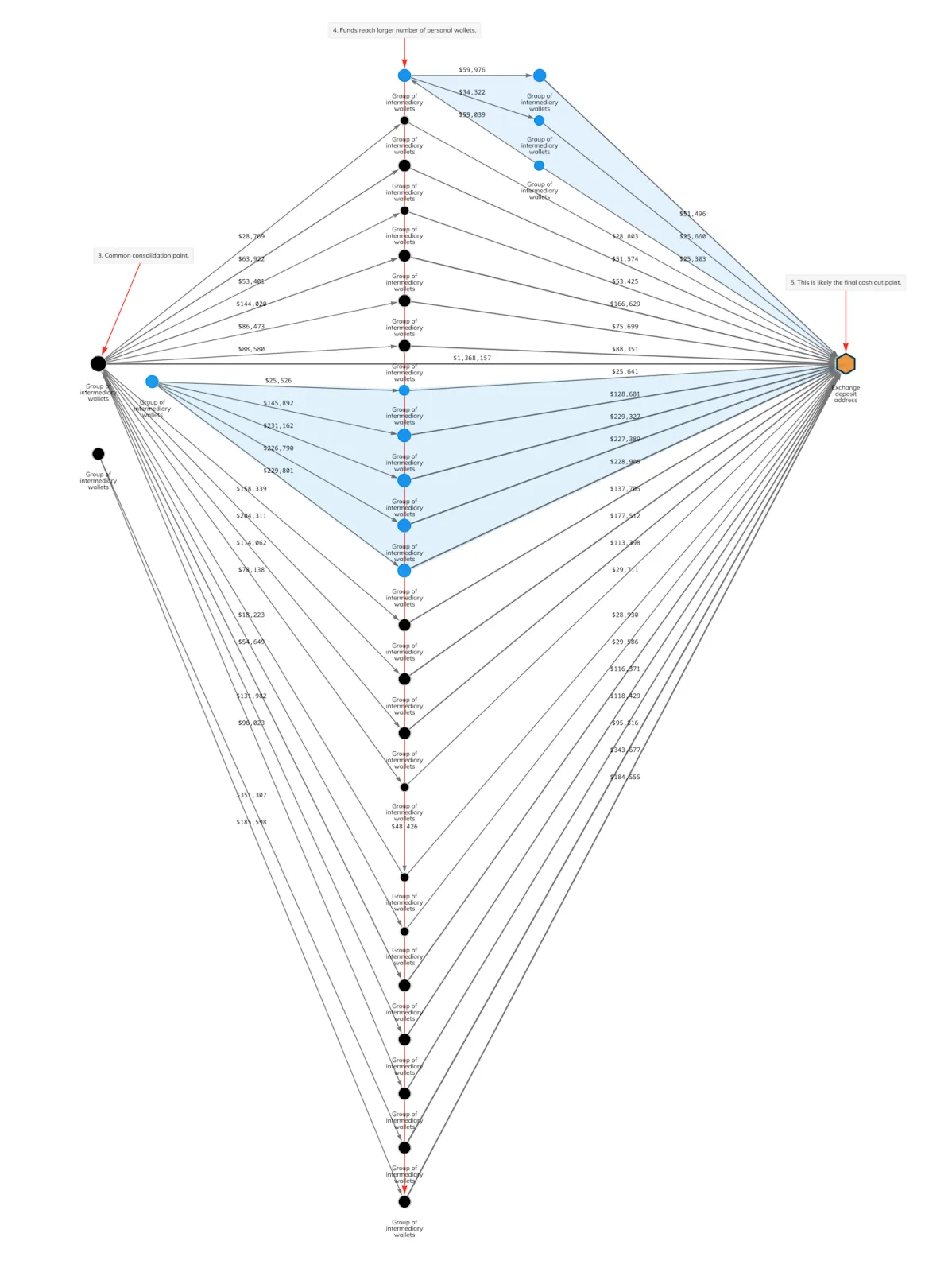

The starting point for the investigation was the addresses on the cryptocurrency exchange itself (stage 1). Cryptocurrency from the four exchange accounts was distributed across nine addresses (stage 2). Subsequently, cryptocurrency from the eighth address was sent to the seventh.

It’s unclear if these addresses are connected to the individuals who stole the fiat funds. The perpetrators may have simply paid the owners of these addresses for goods or services to cover their tracks.

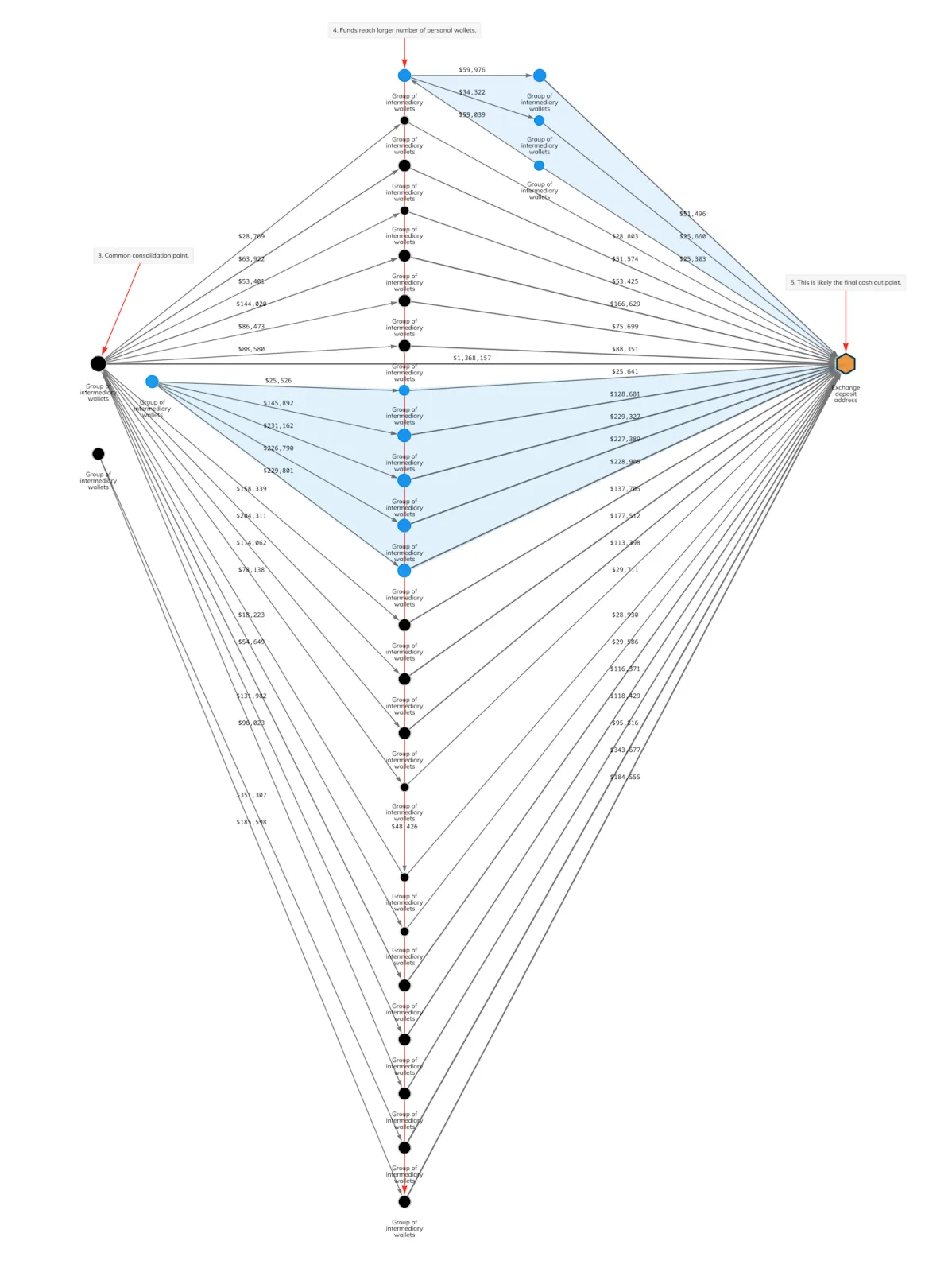

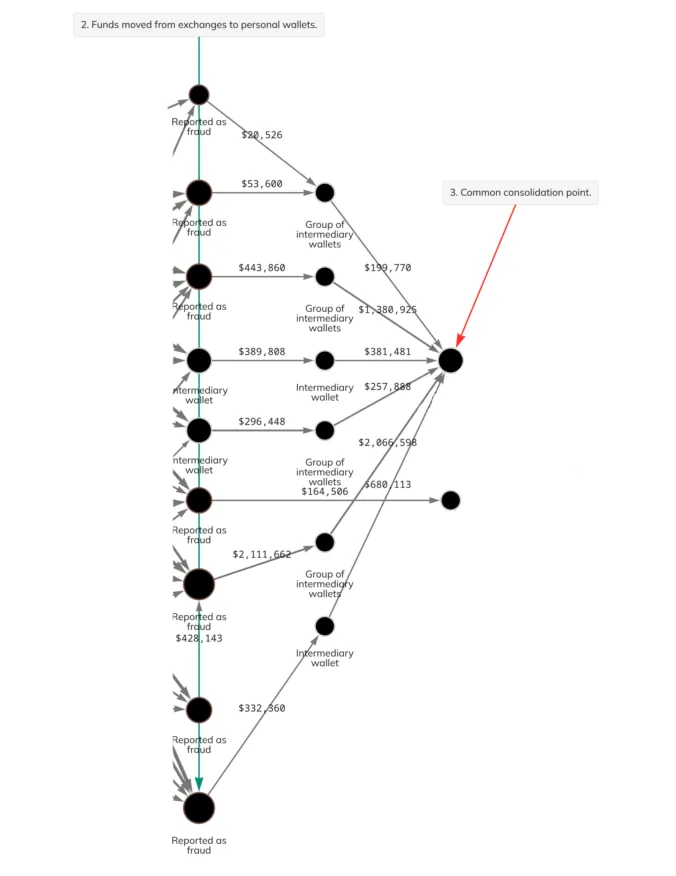

Later, the cryptocurrency from these nine addresses was consolidated onto two addresses (stage 3).

This already indicates a connection between most of the addresses from stage 2 and suggests that they aren’t just random vendor addresses.

After a series of transactions (stage 4), all of this cryptocurrency ended up on the same address, which was an exchange address linked to a specific deposit account (stage 5).

Chainalysis concluded that the owner of this account was the ultimate beneficiary. Based on transaction graph analysis, Chainalysis linked all addresses in the graph to this beneficiary, including addresses through which the cryptocurrency didn’t directly pass in stage 1. These addresses are highlighted in blue in the screenshot.

Thus, from the nature of the operations, conclusions were drawn that the entire cluster of addresses was managed by the same individuals. And their personal information is available on the exchanges where they completed verification.

But could this transaction graph tell an entirely different story?

What if the nine addresses we see in stage 2 are addresses of cross-chain bridges?

In this case, it would mean that the perpetrators withdrew tokens from the exchange through one blockchain and received equivalent tokens in nine other blockchains. For example, they withdrew USDT through the Ethereum network to bridge addresses like Ethereum-Polygon, Ethereum-Aptos, Ethereum-BSC, and so on.

Then, suppose a company accepting payments in USDT across different blockchains wanted to consolidate their USDT on one blockchain, say Ethereum, using the same bridges. This would explain why cryptocurrency from all nine addresses ended up on one or two addresses.

After receiving a large sum on two addresses, this company might distribute it across several addresses for security (“not putting all eggs in one basket”). And when they needed to exchange this sum for fiat, they deposited everything on an exchange address.

This scenario seems equally plausible. If true, none of the addresses in the graph would be connected to the perpetrators. Law enforcement should investigate these matters, but what’s important here is that Chainalysis managed to link a series of addresses to the owner of that account on the exchange appearing in stage 5. And this person’s personal details are known. Any future transactions involving these addresses can be considered linked to that individual.

Why Crypto Swaps Complicate Tracking

The example shows how transactions moving between blockchains can complicate tracking efforts. Chainalysis searched for a beneficiary in the same blockchain where the assets were withdrawn. However, if the beneficiary received assets on a different blockchain, tracking becomes much more challenging.

With cross-chain bridges, it’s somewhat straightforward, as many bridge addresses are public, and an investigator might immediately realize that the real destination lies in a different blockchain. However, using crypto swaps instead of blockchain bridges provides greater privacy benefits:

- Many exchangers assign a unique address for each swap (to avoid mixing client funds).

- Only the exchanger and its client know this address.

- Law enforcement with the proper access could learn where funds were actually sent. But malicious actors are unlikely to track down where your crypto ends up.

It’s especially beneficial to conduct swaps into assets whose recipient addresses aren’t recorded on blockchains, such as:

- Bitcoin on the Lightning Network,

- Litecoin with MimbleWimble protocol,

- Dash using the PrivateSend feature,

- Privacy-focused coins like Monero, Grin, and ZCash, which fundamentally avoid storing transaction details,

- Any assets on the Liquid Network (including USDT).

This way, a malicious actor attempting to find out where you store your funds would come up empty, even if they scanned all known blockchains for a transaction matching your swap.

At Rabbit Swap, we use many liquidity sources, enabling you to swap your assets into a new cryptocurrency, or into the same tokens on a new blockchain, always at the best rates, and preventing unnecessary tracking.